This week, we discuss the general process for the production of red wines. Join us each Sunday in July to get to know how your wine was made. In this week’s article, we will continue to ask “How’d They Do That?” as we discuss the process for the production of red, still wines. The process for red wine production is a very similar 3-step process to that of white wine production: Before Fermentation, Alcoholic Fermentation, & After Fermentation.

Key Differences Between Red & White Wine Production

There are, however, a few notable differences which help to release the color and flavor/aroma compounds that are present in the skins of the grapes.

As noted in the previous article in this series, the juices of all grapes (save for a few odd varietals) is relatively clear. This means that any color in red wines comes not from the juice, but from the skins. The skins are also the primary contributors of tannin (the astringent substance that makes some red wines feel drying to the mouth).

The techniques to extract color and tannin (along with flavor and aroma) from the skins are generally (but not always) omitted or minimized in the production of white wines.

Before Fermentation

The pre-fermentation phase, including the portions that occur before crushing, is often referred to as “CRUSH.”

SORTING

Sorting to remove damaged and/or under-ripe or over-ripe fruit, leaves and other debris, and any array of “MOG” (materials other than grapes — you would be surprised as to what all that might include) may be done entirely by hand, fully by automation, or as a combination of both. The greater the degree of hand-sorting utilized, the higher the cost of production will be.

CRUSHING

Crushing is the process of breaking open the grapes (often called “berries”) so that the juices are released. Crushing is a different process than pressing (which will occur later in the process). Where crushing often does not occur at all in white wine production, it is a standard process for red production as the juices must be in contact with the skins in order to extract the desired color, flavor and aroma compounds (as well as tannin). There is one notable exception to this process in red wine production — a “whole berry” process known as “carbonic maceration.” We will discuss this technique in a future article. Along with crushing, destemming may (or may not) occur; however, stems are often mixed back into the must (the mix of grape juices and solids).

COLD SOAK

Maceration of the skins in the juice is one of the key differences between white wine production and red wine production. During maceration, the grape juice is in contact with the grape skins (as well as the seeds and, if included, the stems). It is during this process that pigment, as well as tannins and a number of flavor compounds, is extracted from the solids and brought into solution with the juice. Maceration occurring prior to fermentation is called “cold soak,” as the must must be chilled to prevent fermentation. At this point, the must is largely water, which is a rather limited solvent. For greater extraction of color, tannin, and flavor compounds, a winemaker may choose to macerate the must during and/or after fermentation, as alcohol is a much more effective solvent. Cold soak/maceration is usually reserved for red wines, but there are some instances (as noted in the previous article) when this process is used for the production of wines from white grapes.

MUST ADJUSTMENTS

In some cases, the winemaker may elect to make adjustments to the must/juice, particularly in terms of acid, sugar, or tannin levels (and even color) — but such adjustments are not permitted in many appellations.

Alcoholic Fermentation

Fermentation is, according to Merriam-Webster, “the enzyme-catalyzed anaerobic breakdown of an energy-rich compound by the action of microorganisms that occurs naturally and is commonly used in the production of various products…”

Alcoholic fermentation is one type of fermentation and is a rather complicated series of chemical reactions. In order to skip the organic chemistry level details, we can simplify the overall process by saying that yeast cells metabolize sugar molecules in such a way as to produce ethanol, carbon dioxide, and heat. Most of the fruit sugars will be converted into ethanol, but some may be broken down into other alcohols, glycerol, a number of different acids, acetaldehyde, or ethyl acetate — of course, some sugars may remain unconverted. Essential steps in the alcoholic fermentation process include:

INITIATION

Fermentation may often be initiated spontaneously, by naturally occurring yeasts that have collected on the grapes. Such spontaneous fermentation by natural yeasts can be a bit unpredictable, especially in areas without an established wine history. In most cases winemakers will use commercially produced strains of yeast to start fermentation in a more controlled manner and yield more predictable results. In such cases, the winemaker will elect to either add sulfur, which kills not only the naturally occurring yeast, but also any fungi or bacteria present, or refrigerate the juice/must, which slows (or even stops) the activity of the yeasts. The primary strain of yeast used is Saccharomyces Cerevisiae, but other strains may be selected to influence the fermentation process or the resulting wine in various ways.

FERMENTATION

Once yeast has been introduced to the juice of the grapes (either naturally or in a controlled fashion), the series of reactions that cause the alcoholic fermentation will be under way. As fermentation proceeds, heat is created, which, left untended, will increase not only the speed of fermentation, but also the temperature of the juice/must.

While white wines are generally fermented at cooler temperatures (50-60℉) to preserve their more delicate flavors, red wines are usually fermented at warmer temperatures to facilitate extraction of desired phenolic compounds (flavor and aroma compounds) and tannin. Lighter red wines may be fermented at a moderate temperature range of 60-70℉, while heftier, more tannic wines may be fermented at a temperatures as high as 95℉. Temperatures in excess of this range run the risk of killing the yeast, therefore prematurely halting fermentation (as well as resulting in very flat, dull flavors in the wine).

CAP MANAGEMENT

As noted above, fermentation results in the release of carbon dioxide. Unfortunately, as the released carbon dioxide rises through the must, it pushes the grape skins (and other solids) up to the top of the fermentation vessel. Keep in mind, the extraction of color, flavor, aroma, and tannin desired for the production of red wine requires the skins to be in contact with the juice — not floating on top of it…

To add to the complication, this floating mass of solids (known as “the cap”) may develop growths of bacteria or even explode from the pressure of the trapped carbon dioxide. As such, the winemaker must keep “the cap” submerged. The most common ways of accomplishing this task are:

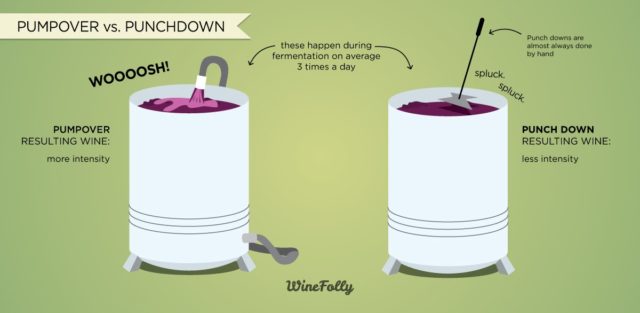

PUNCHING DOWN

In “punch down,” the cap is pushed back into the juice/must.

PUMPING OVER

In “pump over,” juice is pumped from below the cap to above the cap, a process known in French as “remontage.”

RACK AND RETURN

“Rack and return” is an intense variation of “pump over,” in which the juice is drained to a second vessel and, with the “cap” no longer afloat but at the bottom of the original vessel, returned to the original vessel.

ROTOFERMENTATION

“Rotofermentation” requires the use of specialized equipment to ensure that the juice and the solids are kept in solution throughout fermentation (or at regular intervals). This may be accomplished by a stirring/paddle mechanism or by actual rotation/inversion of the vessel.

CESSATION

Fermentation will cease naturally once all of the fermentable sugars in the juice/must has been consumed (leaving no food source for the yeast) or once alcohol levels reach much more than 14% (killing the yeast). The winemaker may choose to halt the fermentation earlier than it would naturally end, often by cooling the wine, but ending fermentation in this controlled fashion may result in residual sugar in wine. Once fermentation stops (either naturally in a controlled fashion), the liquid in the fermentation vessel is wine — but there are still a few more things to do. . .

AFTER FERMENTATION

There are a number of optional processes between the completion of fermentation and bottling. Most producers will utilize most, but not necessarily all of the options discussed below:

MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION

Malolactic fermentation (MLF) is another example of the biochemical processes known as fermentation. In this case, rather assertive malic acid (the same acid in a Granny Smith apple) is converted into gentler lactic acid (one of the acids in yogurt, cottage cheese, and sourdough bread). In addition to softening the perceived acidity of the wine, malolactic fermentation can also help to prevent the development of certain bacteria that feed off of malic acid. While malolactic fermentation is used for only a few white varietals, it is used almost universally for red wines. Malolactic fermentation can occur following or during alcoholic fermentation.

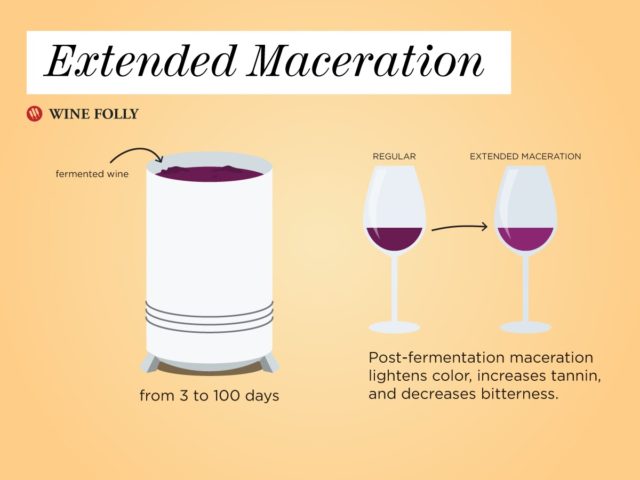

EXTENDED MACERATION

As noted earlier, maceration of the skins on the juice is much more effective in the presence of alcohol than in the presence of water. As such, many winemakers will allow the skins to soak during fermentation. The process may be halted during the fermentation process by pressing (discussed below), but may also be extended to well beyond the end of fermentation. For maximum extraction of phenolic compounds and tannin, the maceration may last several weeks (or longer).

RACKING

A newly fermented wine will be a cloudy (and rather unattractive) proposition. There will also be a mass of solids (the skins, stems, dead yeast cells, etc.) at the bottom of the fermentation vessel. At this point, red wines will be “racked” — a process of allowing suspended solids to settle to the bottom of the vessel and then gently removing the wine. Racking may be performed several times, with each racking resulting in a clearer wine. In red wines, the racked juice is considered “free run” — the juice of the highest quality—and is often kept separate from pressed juices.

PRESSING

For red wine production, pressing extracts any lingering juice from the solids at the bottom of the fermentation vessel. Pressing may be performed between hard surfaces, as with antique wine presses, or with more gentle, bladder-style presses, in which pressure is created by a balloon or bladder filled with air or water. Multiple pressings may occur, with each pressing yielding decreasing valued juice. The solids remaining after pressing are referred to as “pomace” and are often plowed into the vineyard, but may also be used to produce distilled spirits such as grappa or brandy.

CLARIFICATION/FINING/FILTERING

Racking (as discussed above) will remove most of the solids from the wine, but a clearer wine may still be desired. If this is the case, wine may be further clarified by fining or filtering. In fining, an agent will be added to the wine to bond to either proteins or tannins suspended in the wine. The now heavier particles will gradually fall out of suspension and the wine can be racked, as described above. Some fining agents are animal products (gelatin, egg whites, casein, isinglass) and are not suitable for use in vegan wines.

Filtering is a clarification process that involves passing wine through a porous device, thus removing particles that are too large to pass through the openings of the device. Filtering is often used to remove microbes (particularly yeast and bacteria). This can be particularly helpful if alcoholic fermentation was halted before all of the sugar was consumed by the yeast, as fermentation may resume in the bottle; however, filtering does run the risk of removing desirable flavor compounds from the wine. Wines that have not been fined and/or filtered may contain sediment or appear slightly cloudy. This is not considered a flaw, but simply a production choice.

ADDITION OF SULFUR

Sulfur may be added at any point in the process, but is usually done very sparingly to prevent spoilage, browning, or resumed fermentation (in the event that there is residual sugar). Excessive use of sulfur can lead to a number of wine faults.

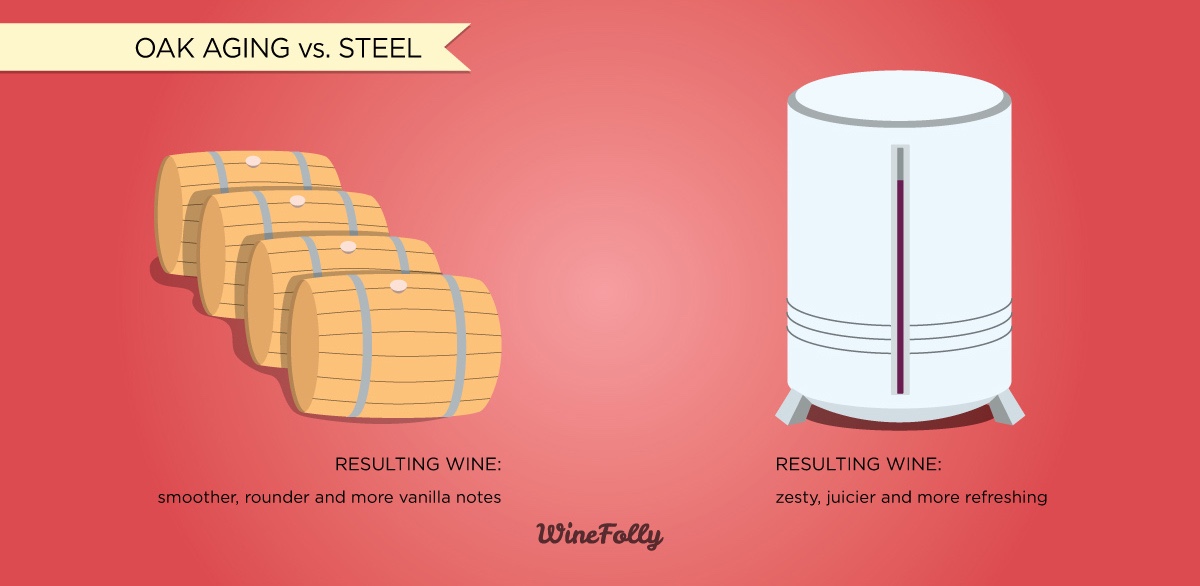

BARREL AGING

Aging wine in a wooden barrel may affect two changes to the wine. First, the wine may pick up flavor and aroma compounds from the barrel. This may result in notes of vanilla, baking spices, coconut, and/or dill, depending on the type and origins of the wood and the age of the barrel (with newer barrels imparting more flavor/aroma). Secondly, the barrel will allow for slow oxidation of the wine.

While oxygen is generally damaging to wine, slow and gradual exposure can help to add complexity to the wine. Barrel aging regimens can be quite complex, utilizing both old and new barrels (with new barrels imparting more flavor and old barrels having more subtle influence), using barrels from different sources (most commonly French or American, but also Hungarian, Slovenian, and Canadian oak (to name a few), each with their own characteristics), employing different levels of “toast” or char on the interior of the barrel, and even using different sized barrels to affect variance in exposure of the wine to the wood (and to the air).

It is worth noting that new barrels from selected French forests can cost as much as $4,000 per barrel! With this cost in mind, several alternatives to barrel again have been developed, including the use of staves, chips, and powders. The effects of these alternatives, of course, are limited to the flavor components that the oak may contribute, and they can tend toward the clumsy, unintegrated end of the spectrum.

BLENDING

Blending is the process of combining several wines into one integrated wine. The wines used for blending may come from different grapes, different vineyards, different vintages, or different winemakers. Blending may be employed to create a more complex, more interesting, and/or more balanced wine, but it may also be used to create a consistent, reliable flavor profile (as is often the case with branded wines).

These are the processes that are most likely to be used for the production of red wines. As with the production of white wines, each one of these processes requires decision by the winemaker — and each will affect the wine that eventually finds its way to your glass. In the next article, we will discuss several methods used to produce sparkling wines. You may be surprised at how many different ways there are to make those tiny bubbles…